Learning From Einstein’s Brain

Einstein’s remarkable brain has an important lesson about balance for all of us in technology and machine learning.

Ellen Petry Leanse, Lucidworks Chief People Officer, has spent 35 years as an innovator at Apple and Google, as an entrepreneur, and advising dozens of Silicon Valley leaders. Her bestselling book The Happiness Hack shares brain-aware paths to focus, connection, and life satisfaction.She frequently speaks on design, equality, neuroscience, and the future of work.

During this year’s virtual Activate, I hosted a 10 minute “Brain Break” so attendees could take a step back from machine learning, AI, and advanced search techniques and learn something new. Not many people would expect a talk on Einstein’s brain to be part of an AI-focused conference, however, insights about his brain are very relevant as we think about the future of AI.

Watch the full session here:

I was delighted with the feedback attendees shared after this talk. It lit up my right hemisphere in all kinds of satisfying ways – you’ll know what that means in a little bit. It got me thinking there was more to share on this topic, which led to this post.

Meet “L” & “R”

Imagine you had two close, trusted friends. One of them – let’s call them “L” – impressed you with their speedy calculations, decisiveness, their precision and self-confidence with whatever answers they sent your way.

Yet, there was a problem with L, despite their many talents. Their mental agility and ability to come up with a fast answer to nearly anything you threw their way made them easy to lean on. The only problem was, they weren’t always right. Their speed and insistence on giving you an answer meant that sometimes they forced their fastest answer onto your question. More than once you’d seen them ‘lock in’ to what they were sure was right, even when it wasn’t.

Your friend “R” was very different. R was reflective, resourceful and responsive, rather than reactive in the way L was. When R heard a question they’d take a moment to consider a range of options rather than deliver the first answer that came to mind. Now, they weren’t as speedy as “L,” nor as confident. More than once you’d seen them waver before offering their thoughts. It was almost as though they were looking for something, even a few things, and weighing them against each other before they suggested their answer.

It was L, though, who showed up with the answers. R seemed more interested in the questions, and the possibilities questions seemed to invite.

L and R got along well when you first met them. Though as you watched them in action, and noticed how they worked together, you realized how frequently L ignored or overrode R’s ideas, even though R’s input was often more valuable than L’s point of view. When L had something they needed to do, or answer, or solve, R came in as a helpful friend, offering ideas and options that L ignored. You noticed R backing down as L became more opinionated and surefire in their ideas. R would still try, yet you felt they weren’t making as strong an effort as L grew more confident and outspoken.

After a while you noticed R not showing up the way they once did. They sort of … faded away, letting L simply do what L wanted to do. You started to realize that L was actually something of a bully. A dominator. And suddenly L’s tendency to grab the obvious answer too fast started feeling more like a risk than the superpower it once seemed like.

What would you do in a situation like this?

Bridging the Divide Between Human and Machine

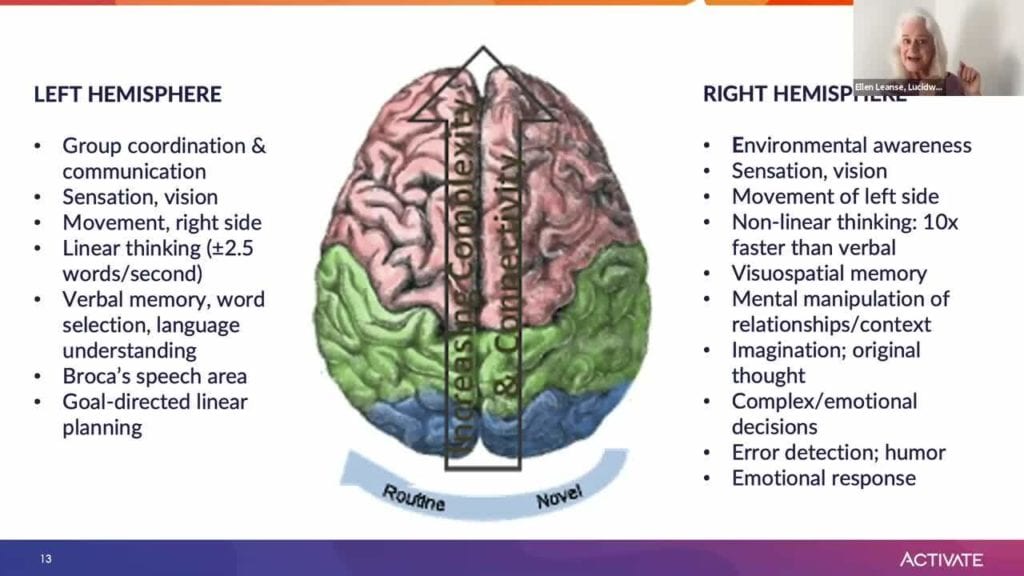

You actually do have these friends, and they’re right there with you at all times. They’re the hemispheres of your brain – L on the left and R on the right – and they work in very different ways. As we move increasingly toward technology, AI, machine intelligence and all other ways we can rely on computation to help us develop concepts and deliver solutions, I believe those R’s in our life become more important than ever.

The left hemisphere – our friend L – is the home of linear, conclusion-driven thought. The left hemisphere arranges logic and information into sense-making patterns in ways that let us construct sentences, convert ideas into order, and apply rules to life’s unending array of scenarios. The left hemisphere resists “on the other hand” thinking. It looks for and locks in to concrete answers, helping us choose next steps and tick things off of whatever list or agenda is driving us forward. Its thought is finite, definitive, linear, and – importantly – conclusive.

On the other hand: the right hemisphere. R is the realm of possibilities, of context and consideration, of imagination and innovation. Original thought and “Aha!” moments rise here. When a question or demand comes forth from the world, the right hemisphere quickly scans for an array of possibilities while the left hemisphere even more quickly looks to deliver an answer. The right hemisphere, interestingly, isn’t all that great at coming up with conclusions or making decisions on its own. The left, however, prefers to. Left to itself, the left will ignore the right – even when the left gets things wrong. We’ve all felt this – those moments when the fast answer turned out to be a wrong answer, and we ask ourselves why we didn’t listen to those other ideas. That “override” is part of the left hemisphere’s way of working – a way that seems increasingly dominant in an increasingly linear, literal, and data-driven world.

Einstein Balances L and R

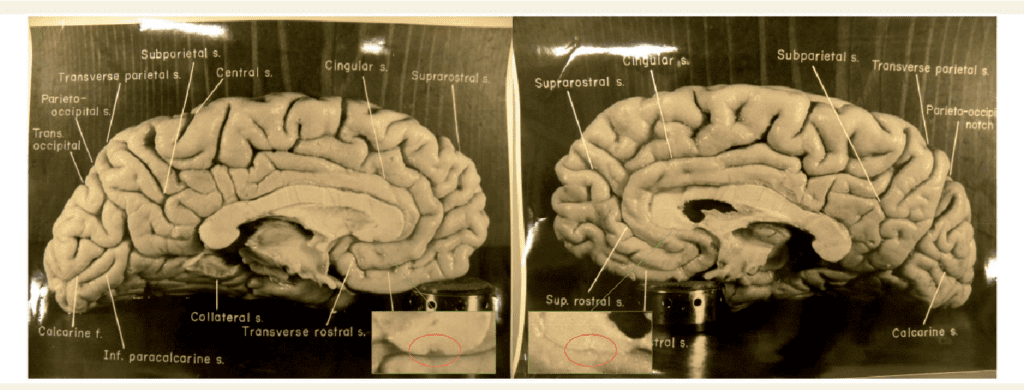

Lateral views displaying the corpus callosum of Einstein’s brain.

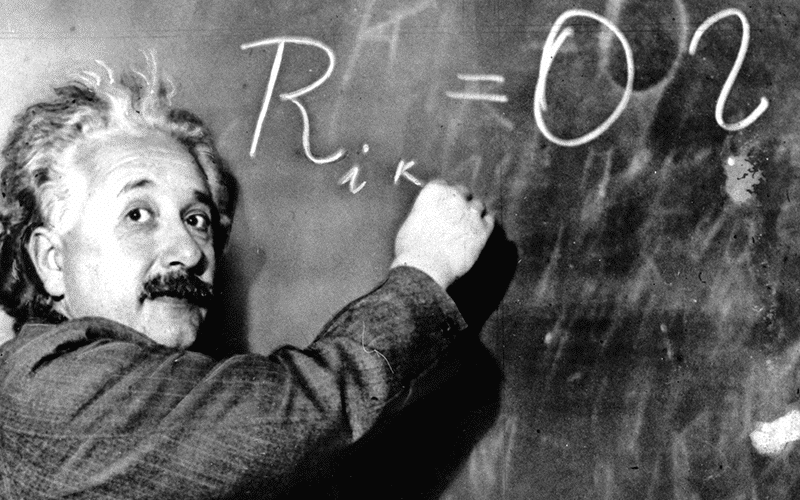

One of the most interesting minds of the last century, however, found a path to balancing both hemispheres – and it served him and our world well. Albert Einstein upheld from childhood a strong preference for the world of imagination, visualization, and ambiguity. He resisted the structure of his early schooling, preferring and, as a teen, taking a stand for education that nurtured his curiosity and gave his mind freedom to wander to non-literal realms.

Boundless work has explored Einstein’s unique cognitive approach and where they led him. Yet recent insights into the brain – studies that deepen our understanding of both its anatomy and functions – make Einstein’s ways of thinking even more fascinating. You see, Einstein turns out to have had a rather unusual brain. Its surface presents a unique array of fissures. It’s unusually asymmetrical (actually lopsided). Yet inside things get extra interesting: he turns out to have had a remarkably large and dense Corpus callosum, the amazing “transfer station” between the hemispheres. Since brain density correlates to usage patterns, one could surmise that that “colossal callosum” demonstrates the hefty exchange of information between its owners’ hemispheres, likely accounting for some of his most revolutionary thoughts.

The high concentrations of a very special type of cell across his cerebral cortex also implies a highly connected brain: one adroit at bridging cognitive divides better than ordinary brains can muster. After all, as the virtual L of an AI-powered world gains momentum, the uniquely human R that so far only we can deliver becomes more important than ever.

You can watch my Brain Break presentation at Activate here and be sure to check out our other educational search and AI videos here.

LEARN MORE

Contact us today to learn how Lucidworks can help your team create powerful search and discovery applications for your customers and employees.