The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: A History of Customer Service

Customer service has a wild history rooted in the boom of innovation that came with the Industrial Revolution. The ebbs and flows of the industry are closely tied to the economic crests and troughs of American consumerism as a whole. Join us on the journey.

It all started with the telephone. In the days of yore, before the automobile, long before the computer and the cell phone and social media, humans had limited options when it came to complaints or issues with, well, just about anything. If you bought something back in the day, chances are you would have to fix it yourself, or if you were lucky and lived close to town, you might be able to bring it back to the local general store to see if the proprietor could help you with anything that wasn’t meeting your needs. These were the days when you got your news from the town crier and when receiving anything through the post took several months. Everything changed when our good friend Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone in 1876.

The beginnings of an industry

The world was obviously wildly different back then. Most goods weren’t commercially bought and sold anyhow – most things you needed at home were usually handmade and totally bespoke. There wasn’t much of a need to call a company and raise an issue about something being broken or defective. So, even though the new fangled telephone was making an entrant into society, it wasn’t a wide-reaching piece of technology and from a customer service perspective, it was being used fairly minimally. But the idea was starting to take hold. Catalogs were just reaching humans with more scale and some items were starting to be purchased through the post. Then, in 1894, the telephone switchboard was invented. Mass production in the Industrial Age was starting to increase. The turn of the century was starting to look like something out of a Jules Verne novel – full of machines and steam and wires and steel.

Customer Service as an industry is fascinating because it’s rooted firmly in the revolutionary change of production and commercialization overall. Without commerce and mass product creation, and the speed-of-light innovation and technology that it took to scale goods and services to the masses, there would be no need for customer service at all. For millennia, service was a privilege of the very few – the wealthy and elite classes that had the money and resources to employ – or force – the work of others to serve their needs. That all changed with the Industrial Revolution – at least in the West. “…gradual improvements in the material life of ordinary people foretold the coming of a time when they would begin to see their material choices expand substantially, and especially in the cities which grew out of the early industrial revolution, the new middle class began to expect to be treated better by businesses courting their custom.”

So much of customer service history starts with this.

The telephone alone and the switchboard that came after it might be cited as the foundational inventions that started to drive the customer service industry, but they would merely be tools for individual communication were it not for the railroads, cars, catalogs, department stores, plastics, and the factories that supported them all. By 1920, when rotary phones started to embed themselves into every household, the middle class in the West had made a roaring entrance into our economic structure. And with it, the accessibility to the goods and services that started to level the playing between the elite and the everyman.

A period of learning

As we know, not every service story ends in success. For a time, through the 1920’s, and with the introduction of the credit line, folks were buying, borrowing and accumulating more than ever before. Department stores started to create customer service sections of the store, where consumers could visit live employees to help them with returns or quick fixes. Companies that wanted to automate more skills in the home – or, “partial customization” – started to make new devices like the sewing machine and the toaster. The need for customer service boomed as these new devices required manuals and questions – and repairs.

But then, the great downswing occurred. The Federal Reserve was new and unprepared for the appetite of the American consumer. In 1929, the stock market crashed, and with it, 12 years of the Great Depression. Innovation slowed, belts tightened, and the bustling high streets of the earlier 20s became ghost towns.

A low period in both customer service and American history.

We won’t delve too deeply into the trough that was those 12 years – the history is grim, but what we learned about how to scale quickly and how to manage innovation at the speed that the consumer desired was paramount. It took a long time – after a then crushing World War – to slowly bring optimism back to the home front. The scrappy can-do attitude and the lessons of what it meant to save and appreciate what we already had at home post-war brought in the next phase of the service journey. Process, efficiency and smarter, computational technology would define the future henceforth. The war room became the contact center (though the term “contact center” wasn’t actually coined until 1983). Welcome to the 1950s and 1960s.

Advancing with new technology

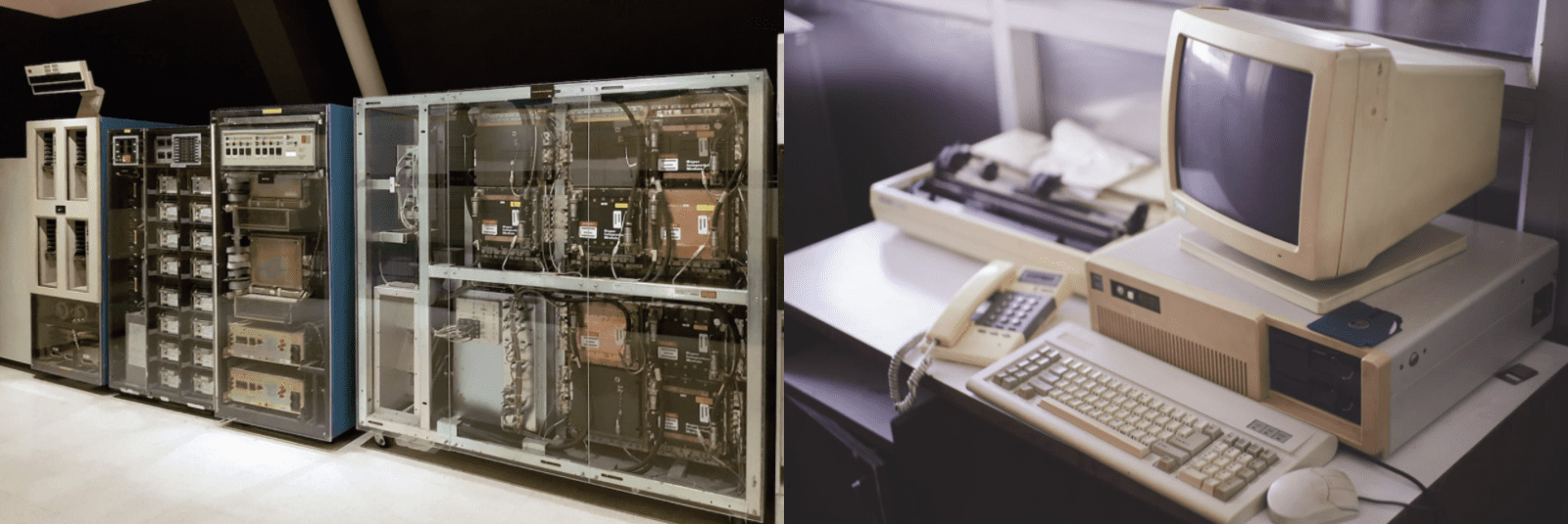

Private Automated Business Exchanges (PABX) of the 60’s were the direct offspring of Automatic Call Distributor (ACD) technology of the 1950’s. ACD systems, built off of the kernel of switchboard tech (that was further finessed during the war), allowed calls to be routed to the next available agent that could help a customer with a problem. The PABX scaled the ACD technology to allow rooms of agents that could be trained by various companies to handle their customer service calls offsite. The telecommunications industry surged in popularity because of the telephone and the television – and was also burgeoned by wartime innovation; the industry was able to invest in new technology like few others.

In 1967, AT&T introduced what would be the next big thing in customer service – the toll-free telephone number. No more need to call collect and speak to an operator – you could call a company directly – it was an irresistible prospect for consumers. This is where the importance of a service agent flourished. Companies could deploy whole departments of agents, trained and employed in-house, to anticipate the customers needs, gather information about their products and upsell more premium offerings. This is where companies really started to recognize the advantages of customer service and how it could drive additional revenue. It wasn’t just about fixing what was broken or returning something a customer didn’t like. This was an opportunity to create a human connection and attain real loyalty. The modern definition of customer service was born.

Computers would cause another major leap forward in customer service innovation.

Computers were now starting to make a massive impact on the way we did business. Companies of all kinds were using these exotic, room-sized machines to process their finances, assess market trends, analyze proprietary data – you name it, we were experimenting with it. We also began “talking” to the computers – and seeing if they could process speech – and talk back. In the 1970s, Interactive Voice Response (IVR) technology was developed because of these experiments. “This led to significant improvements in hard drive technology which in turn allowed customer support departments to store digitized speech on disk, as well as play previously registered messages and move the customer through elaborate phone trees based on their response.”

Early indications of digital transformation

Through the 1980s and 1990s, as customer service exploded through every vertical, analog technology started to shift to digital. The 80s saw the contact center outsourced internationally, and voice technology was improved to increase call deflection and unburden the agents – and the cost that came with them. The Customer Relationship Manager (CRM) was starting to emerge. And of course, the next gigantic change we would all experience – not just in customer service but in every aspect of our lives – the introduction of the internet. Though it wouldn’t be adopted at scale until the 2000s, the internet brought with it not just opportunities to innovate, but also the need to change the entire infrastructure of how we organize information. Things like search demanded that we index all kinds of information; accessibility went from over-the-air to cable trunk lines and internal data centers. Chat was introduced, and Computer Telephony Integration (CTI) coupled with IVR technology helped capture behavioral information about customers calling into a call center – thus the help desk became a service must-have.

The internet allowed for digital connection – and criticism – in real time.

Which brings us closer to now. But not quite. We have a sense memory these days of what things were like in the early 2000s with the rise of the internet, email and social media. The proliferation of software in the cloud, and the maturation of the CRM. We were struggling to manage all of these new channels and looking to the tech industry to help build solutions that could allow us to talk to every customer, on every platform, in real time. The internet was allowing small businesses to thrive, and competition for the big brands – along with more regulation in telecommunications – made keeping the customer more and more difficult.

Social media really put the consumer in the driver’s seat and brands were often embarrassed by poor customer service “tweets” and Facebook messages. Brick and mortar stores started to see tell-tale declines in foot traffic, and people wanted everything, in the moment and at their front door. A lack of investment in customer service innovation went from being a nice-to-have to a full-blown, do-or-die necessity.

Arriving at present day, and looking toward the future

Which brings us, finally, to today. The dust has settled a bit – even though the change is still occurring at an ever rapid clip, we’ve begun to understand how to wrangle all the pieces. In a world that’s now been mangled by a pandemic, and influenced by an obsession with the customer, we understand that the best customer service in the modern world is one that respects the human beings answering the telephone as much as the ones calling in for help. We know that multi-channel is the past and omnichannel is the future. The infrastructure to support a true omnichannel experience connects the journey of a customer and its insights need to be flexible and cloud-based.

Customer service can now be delivered at multiple touch points.

The latest technology to emerge, Artificial Intelligence, is likely best applied, in a business sense, using more guarded machine learning methodologies. All of this, to make the whole experience more personal. In a way, we’ve harkened back to the department store employee. The customer wants something that feels like they’re in-person and one-to-one, having a conversation with someone that’s a real expert in the information they’re seeking. They want someone that knows the products so well, they can anticipate an issue – they want someone that can be proactive instead of reactive. With all the scale and technology the world has offered up in the last hundred years, it really all comes down to the human touch.

LEARN MORE

Contact us today to learn how Lucidworks can help your team create powerful search and discovery applications for your customers and employees.